By Liz Huber

Eulalio Gonzalez Ramirez was born December 16, 1921 in Los Herreras, Nuevo León. Lalo González, better known as El Piporro, is famous for his style of parody in song and lyrics. Prior to his singing and acting careers, Lalo studied to become both a doctor and an accountant. Upon realizing that neither of these two professions was his true calling, he decided to work for a newspaper, El Porvenir de Monterrey, Nuevo León, and later as an announcer for the radio station XEMR in the same city.

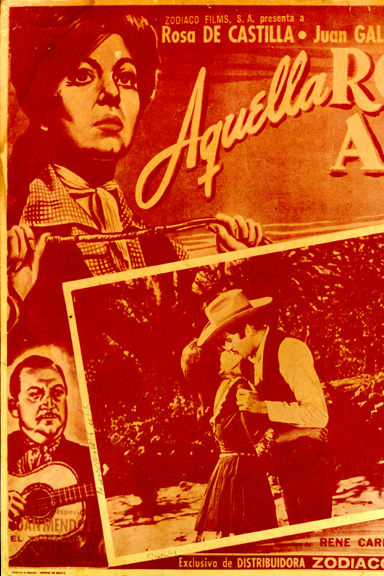

Eventually, Lalo left his home and traveled to Mexixco City, hoping to work as an announcer on another, larger radio station, XEW, on the famous "Voz de América Latina." He succeeded in working for XEW, but instead of a job as an announcer, he found himself working as an actor on the 1950's radio soap operas. Looking back, González says he was incredibly surprised to find himself in this line of work; this was not what he had intended to do with his life. He spoke the voices of many roles on the soap operas, including the romantic male lead, a villain, an old man, and a dramatist. As he was able to imitate more voices, his working opportunities increased until finally he was invited to play a part on the radio series, "Ahí Viene Martín Corona." It is out of this famous series that the famous personality of El Piporro was born. Pedro Infante, acting as Martín Corona, co-starred with Lalo on the series, who played, of course, El Piporro. The series was eventually adapted to make a film by the same title in 1951, "Ahí Viene Martín Corona," also starring Pedro Infante and Eulalio González. He continued his acting career with roles in "El Mariachi Desconocido" (1953), "Mujeres Encantadoras" (1957), "El Rey del Tomate" (1962), and "Los Tales por Cuales" (1964). Lalo was awarded El Premio Cantinflas in 1970 for acting in and directing the 1969 movie, "El Pocho." Some of his famous songs include "Chulas Fronteras Del Norte," "El Taconazo," "El Terror de la Frontera y Genaro Soltero," and "Natalio Reyes Colás."

For more information on Lalo González, click here

While working at the radio station in Monterrey, Lalo developed the style of parody for which he is most famous. He would hear songs on the radio and would imitate or make fun of them by slightly changing the words to the same tune, or by adding his own lyrics inbetween the verses of the songs. One famous example by El Piporro is his version of Rosita Alvirez, whose original author is unknown.

Click below to listen to El Piporro's version of Rosita Alvirez.

Rosita Alvirez--anonymous composer

This version by Lalo González

Click here for more information on Rosita Alvirez.

Another example of this type of parody by El Piporro involves a corrido written and recorded by the well-known singer, Victor Cordero. Lalo took the lyrics and music to the song, "El Ojo de Vidrio" and created his own parodic version by adding comical lyrics inbetween the stanzas. The original lyrics of Victor Cordero appear in yellow text, while the additions made by Lalo Gonzalez appear in light blue.

Click here or use the controller below to listen to El Piporro's version of El Ojo de Vidrio

FONT SIZE="+1" COLOR="#FF6D38">El Ojo de Vidrio--composed by Victor Cordero

This version by Lalo González

¡Ajúa, ajúa! Ojo que no ver, corazón que no siente

decía "El Ojo de Vidrio," y el corredero de gente.

Tenía un solo ojo y ni un alma que lo quisiera.¡Ajúa!

Voy a cantar el corrido

del salteador del camino

que se llamaba Porfirio.

Llamabanle Ojo de Vidrio

lo tuerto no le importaba

pues no fallaba en el tiro.

¡Ajúa! No apuntaba con el ojo bueno porque estaba miope,

pero con el de Vidrio, miraba con aumento. Un bulto bruto,

hacía de cuenta que tiraba a boca de jarro y no le "jerraba."

Se disfrazaba de arriero

para asaltar los poblados,

burlándose del gobierno

mataba muchos soldados,

nomás blanqueaban los cerros

de puros encalzonados.<

Bueno, blanqueaban los que "traiban";

los que no, pos nomás negreaban.

¡Ái viene el Ojo de Vidrio!

gritaba el pueblo asustado,

y a las mujeres buscaba

mirando por todos lados;

dejaba pueblos enteros

llenos de puros colgados.

Cómo le gustaba colgar gente y invitaba a

todos sus amigos a una parranda,

y al final de cuentas los dejaba bien colgados...

con la cuenta. Era travieso, travieso.

Después de tantas hazañas,

al verlo que se paseaba

con su caballo tordillo

frente de la plaza de armas,

lo acribillaron a tiros

sin que le pasara nada.

Decían que estaba forrado

con un chaleco de malla,

las balas le rebotaban

mientras él se carcajeaba.

Se va tranquilo a caballo

sin que nadie le estorbara.

Forrado con un chaleco...

forrado de mugre: nunca se bañaba,

por eso no entraban las balas.

La cáscara guarda al palo.

Bajaron tres campesinos

y allá del cerro escondido,

traiban al Ojo de Vidrio

picado de un coralillo,

venía ya muerto el bandido

sobre el caballo tordillo.

The original corrido by Victor Cordero tells the story of a bandit, more specifically a highway man, ("salteador"), named Porfirio, who was known as The Glass Eye because, in fact, he had one eye of glass. It didn't bother him that he had an eye of glass because it didn't affect his shooting; he never missed when he shot. He disguised himself as a mule driver and traveled into the towns. He made fun of the government and killed many soldiers, making the hilltops white with the underwear of the numerous dead soldiers. A typical corrido speech event occurs in the third stanza when the town cries out, "Here comes the Glass Eye," and the women look around on all sides, because he would leave entire towns completely filled with hung men. After so many deeds such as this had happened, he would ride up on his dapple gray horse in front of the town's square. The people would riddle him with bullets, but none passed through. They say that he was armed with a bullet-proof vest because the bullets would bounce around while he guffawed. He would leave tranquily on his horse with no one stopping him. At the end of the corrido, three peasants came out of their hiding place in the hills, leading the Glass Eye. He had been bitten by a craw snake, and the dead bandit was lead into town on top of his gray horse.

Lalo González adds his own twist to the story by interrupting the stanzas with verses of his own. Before the song begins, he introduces the bandit as the man with an eye that doesn't see and a heart that doesn't feel. He scares the people, running them off. He has one eye and no soul that would want an eye. Following the first stanza, González begins to make fun of the man, saying that he didn't aim with the good eye that he had because he was myopic, and the glass eye served as something of a lens, which helped to increase his vision. After the second stanza, in which Cordero mentions the hilltops made white by the underwear of the dead soldiers, González jokes that the soldiers wearing underwear made the hilltops white, but the ones who weren't wearing any made the hilltops black. Following the third stanza, which discusses the fact that entire towns were filled with hung men after the Glass Eye left, el Piporro says that even as much as the bandit liked to [literally] hang people, he would also invite his friends to go on a drinking binge party, and then leave them "hanging" with the check. González jokes that the Glass Eye was mischievious, ("travieso") in this way. Finally, after the penultimate stanza, which talks about the bullet-proof vest the Glass Eye wore to protect him, González says that what really protected him was a layer of dirt and filth that resulted from a lack of bathing. This dirt protected the bandit from the bullets as bark protects a tree, according to el Piporro.

In addition to using the lyrics of other Mexican singers, González would also compose original songs that reflected his sense of humor. The topics and points of parody vary in each of his songs. Because El Piporro was primarily a Mexican artist, the aim in many of his songs was to appeal to the Mexican population. He accomplished this by siding with their prejudices and incorporating a Mexican outlook and their beliefs into his music. "Natalio Reyes Colás" is one of El Piporro's corridos which deals with the subject of immigration and something the Mexicans refer to as apochamiento. Apochamiento was the name Mexicans gave to the process by which Mexican immigrants became increasingly American in their lifestyle and beliefs after immigrating to the United States. In this corrido, Natalio Reyes Colás is a pocho, or a Mexican who has succumbed to apochamiento. Natalio, like other pochos, is considered to be a traitor to his Mexican heritage by selling out to material goods and American ways. The title of the song, the spanish translation of Nat King Cole, introduces the parody to come.

Click here or use the controller below to listen to Natalio Reyes Colás

Natalio Reyes Colas--composed and sung by Lalo González

The story line in el Piporro's "Natalio Reyes Colás" is as follows: Natalio is born in Tamulipas and grows up on the Rio Grande. He has a girl friend, kind of cute but kind of fat, and her name is "Patrita." Natalio makes her a promise, and she asks him not to forget her, but then he moves to the United States, where he meets another girl, "Pochita." Here the musical style changes from the typical Mexican corrido to sound like American rock and roll. Pochita Americanizes Natalio's name by shortening it to Nat, and he quickly discards his Mexican heritage, stating that he no longer wants to polka with the accordian. He has forgotten about Patrita and now sings to Pochita like Nat King Cole. Eventually, Pochita leaves him because he cannot sing or dance; he is disappointed with her because she only cooks American food, (ham and eggs and hamburgers with ketchup), and he is used to tortillas and chile. Natalio returns to Mexico and Patrita, and even though she's a little ugly, it's alright.

El Piporro uses this song as a parody of the pochos who leave their homes in Mexico to live in the United States. Even though Natalio made a promise to Patrita, (a name which suggests the connection to his homeland, or patria), he soon forgets about her upon arriving in America. The abrupt change in the music, from the traditional Mexican corrido to 1950's rock and roll, is another way González makes fun of the pochos. At this point in the song, the lyrics switch to become a mix of spanish and english. El Piporro mispronounces the word "bracero," which means a Mexican laborer or farmer who uses his arms in his work, and uses a mocking tone to convey his contempt for Mexican ways. Instead of wanting to polka with the accordian, a dance and musical instrument that usually accompany traditional corrido music, he sings to Pochita like Nat King Cole. (Remember also that Pochita had changed Natalio's name to the more American-sounding, Nat.) At the end of the song, Natalio has realized the error of his ways; he is tired of American food and American women. Even though Patrita is "feaita," or a little bit ugly, he doesn't mind. Natalio returns home, to his Mexican culture and his Patrita.

Link to Rosita Alvirez home page