Richard Wagner is one of the most influential composers, not just of the nineteenth century, but in all of art music. His new, daring way of writing harmonies shocked the public, and other composers of the time period (and afterwards) definitely took notice. There were two main ways that contemporaries of Wagner reacted to his work: they either imitated him and tried to be just as enterprising with their own harmonies, or else they worked hard to make sure their music was as different from his as possible. (Of course, this latter example is still an example of influence, although it’s really a lack-of-influence. Shutting the door on certain musical possibilities admits a certain anxiety about Wagner on those composers’ parts.)

Two composers who tipped their hats to Wagner by quoting his music in their own works are Claude Debussy and Alban Berg. However, they paid their respects to Wagner in very different ways. The first piece to be discussed one of Debussy’s: “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk,” from Children’s Corner (1908). This particular piece is based upon the dance of a golliwog doll, or a puppet based on a happy-go-lucky black stereotype of the nineteenth century. Ignoring the obvious racial issues that this provokes, the song is meant to be lighthearted and funny, imitating a puppet’s dance. Debussy imitates the clunky music of a hurdy-gurdy with his cake walk.

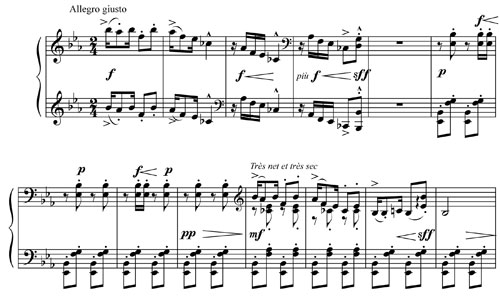

The beginning of “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk” is shown below.

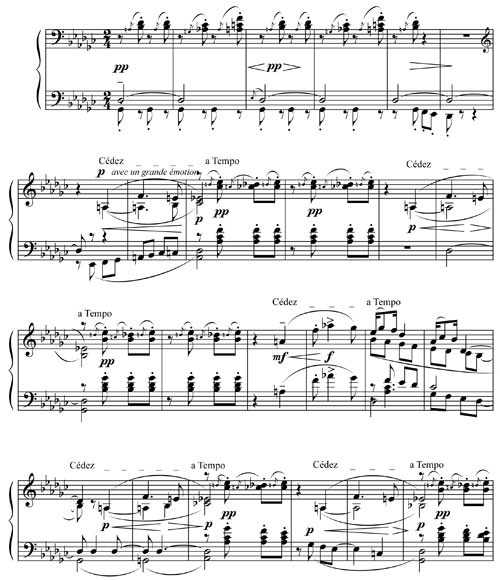

After the four-bar introduction, the general flavor of the piece is put forward: left hand accompaniment with a syncopated right hand melody. This music is reminiscent of ragtime songs, which were popular at the time. However, a big change occurs sixty-one measures into the piece. Suddenly the ragtime music stops, and we hear a long, legato phrase that seems a bit familiar. In the middle of “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk,” Debussy has inserted the opening phrase of Tristan and Isolde! He uses only the Longing motive, and excludes perhaps its most salient feature: the Tristan chord at the end. Instead, Debussy accompanies the final D-sharp (written here as an E-flat) with both non-triadic chords and minor-minor seventh chords. The Longing motive appears four times, as is shown below.

Debussy trivializes Wagner’s dramatic theme by including it in such a piece as “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk.” After each of the four statements of Longing, the music returns to the blithe, staccato eighth notes of the golliwogg’s dance.

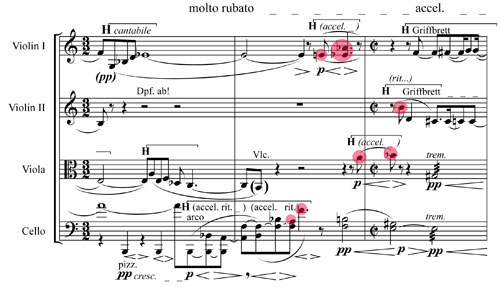

The second piece that pays tribute to Tristan and Isolde is the sixth movement (Largo desolato) of Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite. The entire piece is very forward-looking, harmonically. It uses twelve-tone rows and avoids a tonal center during most of its duration. In the middle of this movement, Berg includes a quotation from Wagner. Once again, the part of the opera that is quoted is the Longing motive, but this time it is allowed to continue, and leads into the Desire motive. This is shown below (the Wagner quotation, since it moves back and forth between the various string parts, is highlighted in red).

Berg is more faithful to Wagner’s harmonizations than Debussy was. (Though both composers do use the original pitches of the motive without transposition.) The intersection of Longing and Desire is indeed harmonized with a Tristan (half-diminished seventh) chord, and the end of the Desire motive uses a dominant seventh chord. These are the harmonies that Wagner wrote to accompany the motives in Tristan and Isolde.

However the most significant difference between the two settings has to be one of mood. While Debussy uses the Wagner quote as a joke, Berg is completely serious about the way he sets it. The disjunction between the texture of “Golliwogg’s Cakewalk” and the Longing motive is so pronounced that it becomes immediately humorous. On the other hand, the Wagner music fits almost seamlessly into Berg’s slow movement. The listener must be familiar with Tristan and Isolde to even realize that Berg is quoting someone.