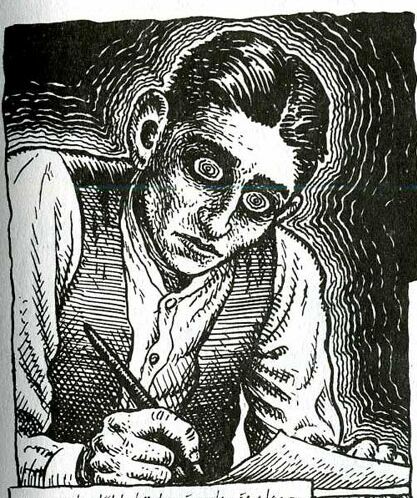

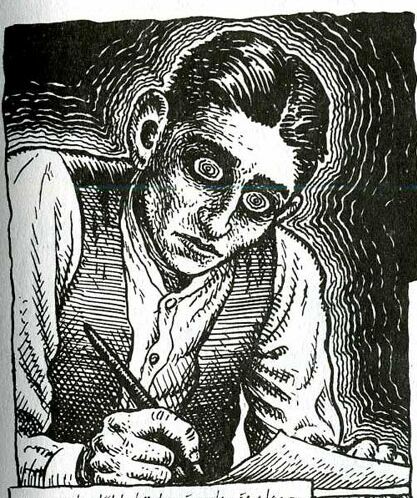

The first sentence of Franz Kafka’s “The

Metamorphosis” strikes the reader with incredible force. As if the reader

has gained entry into his own “unsettling dream,” there is an immediate

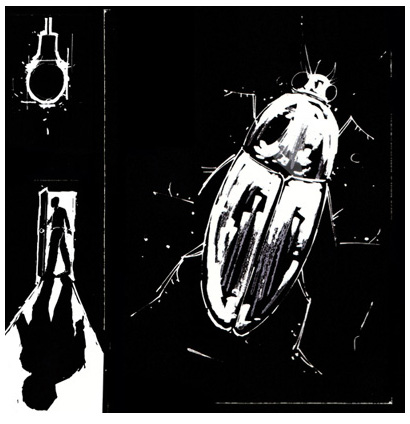

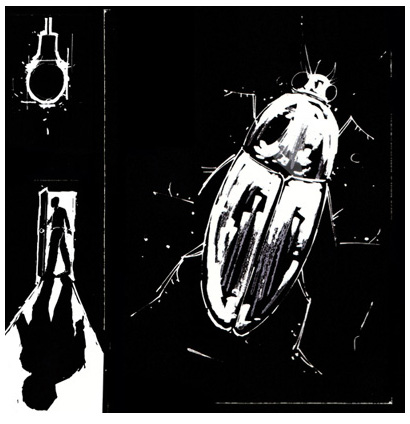

revelation that Gregor is “changed into a monstrous cockroach in his bed”

(210). As often occurs in dreams, the reactions are not what might be expected,

and Gregor’s calm feels like running feels in some chase and pursuit dreams,

like a churning effort that takes us nowhere.

A useful analysis of the story almost has to,

as Gregor does, take the metamorphosis in stride, and focus on the other aspects

of the story. The first part introduces family matters, matters of business,

the rather listless and complaining aspect of Gregor, who, it seems, is imprisoned

by his life well before he becomes the monstrous vermin. This is the broad view,

over which is laid the subtleties for which Kafka is celebrated: the gestures that reveal the instinctual reactions of family and boss, the voices that come

from a depth in the characters that seems primal, the foci that Gregor, seemingly

irrationally, takes on the situation. My presentation of part one of “The

Metamorphosis” will indicate the small moments in the text, with an effort

to show how they might relate to the larger thematic elements. It is hoped that

by shifting the focus from the first sentence to the story’s more primary

concerns, that students will be guided in the remainder of the reading to evaluate

aspects of family, business, and the choices Gregor has made in his pre-vermin

life, and that readers will thus be able to arrive at a more sophisticated conclusion

about Kafka’s concerns in the story.

The story.

First paragraph is all that anyone ever remembers.

Let’s say, though, that the story is about alienation in the 20th century.

Here, turned into a kind of alien—alienated from his own body. But also

distanced from the family, from social institutions (i.e., the workplace, etc.)

2nd paragraph gets more interesting. The calm

attitude with which Gregor is able to assess his situation. No dream. One

of the first objects is the picture hung up of the lady in furs. How is it that

she too has been turned into an animal? Is this Gregor’s fantasy woman?

Is this his “art” from which he is also alienated?

Exclamation point after “If only I didn't follow such an exhausting profession!”

(not after his "numerous legs").

Gregor’s rational attempts to explain away

his condition. All goes back to his horrible job, which gives him no satisfaction.

It is here that we find out about the family debt, without which he would have

quit long ago.

Another exclamation point with an epithet. When

he looks at the clock for the first time. Time, order, schedules, the ledger

sheet, becoming the new god, the "Great heavenly Father!" (211).

One of the significant elements of the story is the voices with which people

speak. The mother—"the mild voice." Gregor’s voice—“with

a painful and insuppressible squeal blending in as if from below” (2001).

Or is the Hofmann translation: "without doubt his own voice from before, but with a little admixture of the irrepressible squeaking that left the words only briefly recognizable at the first instant of their sounding, only to set about them afterwards so destructively that one couldn't be at all sure what one had heard" (212).

Little bits such as the father’s knocking

“feebly, but with his fist.” Then he called "again in a lower octave.” (212). His sister whispered. The manager called

in a friendly voice. 216—“that was the voice of an animal's voice.” 2006--

The manager’s “Oof” that ehoes through the stairwell.

The meticulously careful, realistic description

of Gregor getting out of bed takes this from the realm of the unreal to the

mundane, the everyday. As if the ultra-absurdity of everyday life is taken for

granted.

218. It is after the manager (voice of god?)

has leveled his list of accusations that the explanatory voice of Gregor comes

out without editing, unmediated. To clear up what he feels is a misunderstanding.

Bottom of 216-- he felt included once again

in human society "within the human ambit" and, without really drawing a sharp distinction between the

doctor and the locksmith, "he hoped for magnificent and surprizing feats."

217--The expectancy that he should have been

cheered on.

217 . How to read the portrait of Gregor in his

military uniform, from his period in the army?

218. Manager—"twitching shoulder and

with gaping lips" (also like an animal?).

220--As Gregor is being forced back into his

room, the issue of voice, or even sound, comes back. In the dreamike setting, this becomes even more unreal as "the sound to Gregor's ears was not that of one father alone" (220). |