Bengal Past and Present, 117 (1998): 57-80.

The Representation of Sati:

Four Eighteenth Century Etchings by Baltazard Solvyns[*]

Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr.

When the Flemish artist Baltazard Solvyns[1] arrived in Calcutta in 1791, the debate over sati was just beginning as missionaries, among others, condemned official toleration of the "dreadful practice" and called for its suppression. Of all Hindu customs, none more fascinated--or appalled--the Europeans than "suttee," the practice of widow-burning. The term sati is Sanskrit for "virtuous woman," but is used principally to refer to the faithful wife who "becomes sati" through self-immolation on the funeral pyre of her husband. Europeans erroneously took the word to mean the practice itself, and suttee, the European corruption, has become the conventional term for the wife's self-imolation. Solvyns uses neither suttee nor sati as terms in his description, but rather the Sanskrit word he spells phonetically from Bengali pronunciation. The practice by which the wife joins her husband in the flames and becomes sati is termed sahamarana, "dying together," also known as sahagamana--Solvyns's Shoho-Gomon--meaning "going together."[2]

The practice was prevalent in Bengal in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Benoy Bhusan Roy, in Socioeconomic Impact of Sati in Bengal, writes that suttee was most frequent among Brahmins, but that the practice was found among the families of lower castes that had distinctive positions in wealth or property. Indeed, the possible increased frequency of suttee may have reflected aspiration to higher social status among upwardly mobile sudra families.[3] But, as official records in the early nineteenth century reveal, suttee was not limited to the more affluent. The practice was to be found among many castes and at every social level.[4]

Among European travelers in India during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, no description was complete without reference to suttee--preferably with at least one eye-witness account. Pierre Sonnerat, who traveled in India in the 1770s, describes the practice and provides an engraving of an Indian woman going to be burned with the body of her husband.[5] Another French traveler, Grandpre, writing of his experience in Bengal in 1789 and 1790, relates his own unsuccessful effort to rescue a beautiful young woman who was to become sati, and notes that the practice of suttee was particularly "horrible" in Bengal.[6] Failed intervention was a frequent theme in European accounts, as in Thomas Twining's description of his thwarted effort to prevent a suttee some 60 miles outside Calcutta in 1792.[7] Confirming accounts of restraints to prevent the woman's escape, Edward Thompson writes in Suttee that "Especially in Bengal, [the woman] was often bound to the corpse with cords, or both bodies were fastened down with long bamboo poles curving over them like a wooden coverlet, or weighted down by logs."[8]

Most instances of suttee were described as "voluntary" acts of courage and devotion. But there were surely cases involving the use of force, drugs, or restraints. In "An Account of a Woman burning herself, By an Officer," appearing in the Calcutta Gazette in 1785, one of various instances of suttee reported periodically in Calcutta newspapers, the observer describes the woman as likely under the influence of bhang or opium but otherwise "unruffled." After she was lifted upon the pyre, she "laid herself down by her deceased husband, with her arms about his neck. Two people immediately passed a rope twice across the bodies, and fastened it so tight to the stakes that it would have effectually prevented her from rising had she attempted."[9]

The Reverend William Ward, a Baptist missionary at Serampore, near Calcutta, and a contemporary of Solvyns, recounts his own witness of the practice (which he terms suhu-murunu ), as well as reported instances in the area of Calcutta. William Carey, the famed author of the Dictionary of the Bengali Language and Ward's colleague at the Serampore Mission, undertook a census in 1803 of suttees and counted 438 that had reportedly taken place that year within a thirty mile radius of Calcutta.[10]

In contrast to the expressions of horror in most accounts, an American merchant, Benjamin Crowninshield, described the suttee he witnessed while in Calcutta in 1789 with "extraordinary detail" and "great sensitivity."[11] In his ship's log, he concluded his sober account: "Whether it is right or wrong, I leave it for other people to determine. . . . [I]t appeared very solemn to me. I did not think it was in the power of a human person to meet death in such a manner."[12] Similarly, Maria Graham, in her Letters on India, published in l8l4, wrote sympathetically and without judgment of the practice--particularly remarkable at a time when European missionaries and Indian reformers were mounting their campaign againt suttee.[13]

Within the city of Calcutta, under jurisdiction of British law, suttee had been prohibited since 1798, but outside Calcutta, the "dreadful practice" flourished in Bengal--indeed, some said, in epidemic proportions. As the debate over widow-burning intensified, officials took steps to suppress the practice in 1812, with a distinction between "legal" (voluntary) and "illegal" (involuntary) suttee.[14] Its complete abolition came under Lord William Bentinck through Regulation XVII of the Bengal Code, December 4, 1829, declaring the practice of suttee, whether voluntary or not, illegal and punishable by the criminal courts.[15]

The European fascination with suttee, expressed through traverlers' accounts and in the debates over official policy, was mirrored in visual representations by both amateur and professional artists. Among the earliest portrayals of suttee is an engraving, 1598, to illustrate the account of the Dutch traveler, Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563-1611), who lived in India from 1583 to 1588. The print shows a widow, with arms raised, stepping off into a pit in which her husband is consumed in flames.[16] The Hindu widow again leaps onto the pyre in the 1670 frontispiece engraving for the book by the Dutch missionary Abraham Roger.[17] The early portrayals of suttee in prints were based on travelers' descriptions, such as those by Linschoten and Roger, and are often highly fanciful, but by the late eighteenth century European artists in India were drawn to the subject and its powerful imagery. Tilly Kettle (1735-1786) painted the serene young widow bidding farewell to her relatives.[18] Johann Zoffany (1733-1810), in one of at least three paintings he devoted to the subject, depicted suttee as a "heroic act," as Giles Tillotson notes. "The widow here is not a sentimental figure inviting pity, but a moral exemplar to be admired."[19] The paintings by Kettle and Zoffany are idealized, and it is unlikely that they were based on first-hand observation, but in the early 1780s, William Hodges (1744-1797) witnessed a suttee near Banaras and made a drawing at the scene. He subsequently completed a painting, "Procession of a Hindu Woman to the Funeral Pile of her Husband," that served as the basis for the engraving accompanying his description in Travels in India.[20] There is in Hodges's depiction a somber atmosphere of saddess, but it too is idealized and draws Solvyns's criticism as not being "correct."[21] A later painting, 1831, by James Atkinson (1780-1852), is also romantic and conveys in its portrayal of the beautiful young widow an overtone of the erotic that was so often associated with the depiction of suttee. Archer and Lightbrown suggest that Atkinson "probably intended to express sympathy with the plight of young Indian womanhood condemned by inexorable custom to premature death."[22] Many European portrayals of suttee, as in written accounts, reflect ambivalence--admiration for the courage of the virtuous woman and sympathy for the victim of a heathen rite--but characterturist Thomas Rowlandson uses his 1815 engraving, "The Burning System," as an attack upon the government for its complicity in permitting "voluntary" suttee.[23] And over the course of the nineteenth century, with imagery of horror, missionary tracts and journals frequently depict suttee as the symbol of benighted India and Hindu "superstition."[24]

Solvyns, in his portrayal of suttee, seeks to record faithfully and accurately as an observer what he witnessed "in order to give fullness, truth and spirit to the resemblance." But Solvyns, no less than his contemporaries, brings a mixture of admiration and sympathy and condemnation.

Born in Antwerp in 1760, of a prominent merchant family, Solvyns had pursued a career principally as a marine painter until political unrest in Europe and his own insecure position led him to seek his fortune in India. India in the late eighteenth century had attracted a number of British artists who found a ready market for their works among the Europeans of Calcutta and Madras and in the courts of the Indian princes. Thomas Hodges, and later Thomas and William Daniell, sold landscapes, but the most handsome profits were to be made in portraiture, and here such painters as Tilly Kettle, Thomas Hickey, and John Zoffany enjoyed the patronage of nabobs and nawabs alike.

Solvyns was adept at neither landscape nor portraiture, and upon his arrival in Calcutta in 1791, he became something of a journeyman artist. He provided decoration for celebrations and balls, cleaned and restored paintings, and offered instruction in oils, watercolor, and chalk. The decoration of coaches and palanquins apparently provided Solvyns his steadiest income, but hardly the success and sense of accomplishment he clearly sought. In 1794, inspired by Sir William Jones, Solvyns announced his plan to publish A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs and Dresses of the Hindoos.[25]

With a sufficent number of subscribers to begin, Solvyns set out to record the life of the native quarter of Calcutta, or "Blacktown," as it was then called. He approached his task as an ethnographer, drawing his subjects from life and with more concern for accuracy than asethetics. The collection was published in Calcutta in a few copies in 1796, and then in greater numbers in 1799. Divided into twelve parts, the first section, with 66 prints, depicts "the Hindoo Casts, with their professions." Following sections portray servants, costumes, means of transportation (carts, palanquins, and boats), modes of smoking, fakirs, musical instruments,[26] and festivals and religious ceremonies of the Hindus. In the last section are four etchings depicting suttee.

The project proved a financial failure. The etchings, by contemporary European standards, were rather crudely done; the forms and settings were monotonous; and the colors were of somber hue. They did not, in short, appeal to the vogue of the picturesque. But the subjects were themselves compelling, and London publisher Edward Orme brought out a pirated edition of 60 prints "after Solvyns," redrawn for appeal and colored in warm pastels. The volume, The Costume of Indoostan,[27] through various printings, was highly successful, but Solvyns derived no gain and suffered, as he later wrote, "abuse . . . made of his name and of his works."[28]

In 1804, Solvyns left India for France, and soon after his return to Europe married Mary Ann Greenwood, daughter of an English family resident in Ghent. In Paris, drawing upon his wife's resources, Solvyns prepared new etchings and produced a folio edition of 288 plates, Les Hindous, published in Paris between 1808 and 1812 in four elephantine volumes.[29] In his introduction, Solvyns writes that while European scholars have done much "to dispel the darkness which enveloped the geography and history of India, . . . its inhabitants alone have not yet been observed nor represented with the accuracy which is necessary to make them perfectly known. . . ." To rectify this situation, he offered to the public Les Hindous, " the result of a long and uninterrupted study of this celebrated nation."[30]

The drawings from which are engraved the numerous plates . . . were taken by myself upon the spot. Instead of trusting to the words of others, or remaining satisfied with the knowledge contained in preceding authors, I have spared neither time, nor pains, nor expense, to see and examine with my own eyes, and to delineate every object with the most minute accuracy . . . .

I admitted nothing as certain but upon the proof of my own observation, or upon such testimony as I knew to be incontrovertible. I have wholly neglected the testimony of authors who have treated these subjects before me, and have given only what I have seen, or what I have myself heard from the mouth of the natives the best informed and most capable of giving me true instructions upon the subject of my inquiries.

What I have said of the text, may also in some degree be applied to the prints themselves, in which I have purposely avoided all sort of ornament or embellishment; they are meerly representations of the objects such as they appeared to my view. . . .[31]

The Calcutta edition labeled each etching by name, but Solvyns published the descriptive text separately in a small Catalogue with brief entries.[32] For the Paris edition, however, Solvyns accompanied each etching by an expanded descriptive text, in both French and English.

In 1799, in his Catalogue for the 250 etchings of the Calcutta edition, Solvyns writes that suttee--what he terms "Shoho Gomon"--has been "often described and is so generally known" that he need not provide a separate account of the ceremony itself. But perhaps with a larger, less knowledgeable audience in mind for the Paris edition in l8l0, Solvyns felt compelled to offer a description of the suttee to which he was eye-witness.

For each suttee etching reproduced below, Solvyns's entry for the 1799 Catalogue is followed by the more extensive text (identified by volume, section, and plate) of the Paris edition, with my commentary on Solvyns's portrayal.

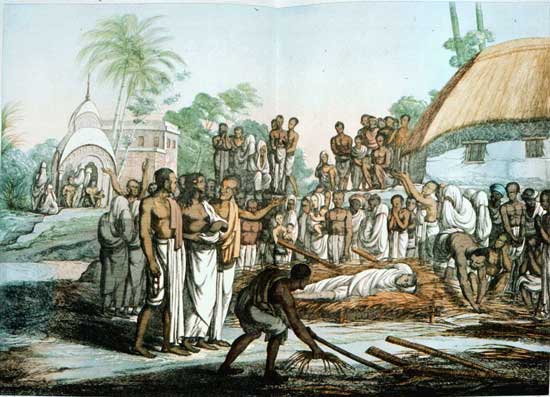

Sahagamana

Calcutta: Sec. XII, No. 13. Shoho Gomon,--Women burning themselves with the Corpse of their Husband.--This ceremony has been so often described and is so generally known, that an account of it would be superfluous.

Paris: II.9.1. SHOHO-GOMON.

A WOMAN BURNING HERSELF WITH THE CORPSE OF HER HUSBAND.

This ceremony, which is closely connected with one of the most singular dogmas of the Hindoo religion, appeared to me of sufficient importance to require several plates in order to represent it with all its circumstances and most minute details, notwithstanding that it has been already described in several works. The Asiatic society has given to the public many different Memoirs upon this subject,[33] and Mr. Hodges has represented it in an engraving,[34] but not very correctly. The truest description is that which Mr. Shakespeare, one of the directors of the East-India company, has published in a small pamphlet printed in England about the year 1790.[35] For my part, I shall only say what I myself have been an eye-witness of: the principal functions of this melancholy ceremony are prescribed in the sacred writings of the Hindoos. The woman who has made the vow of burning herself with the dead body of her husband, begins by bathing; after which she dresses herself in entirely new apparel; the priests then paint her face with minium[36] or red oker, with which I have been assured they mix gunpowder and sulphur, no doubt to shorten the sufferings of the unfortunate victim of their superstition. When this is done, she takes in one hand an evergreen herb called Cusa [kusa],[37] and some water in the other; and while the Brahmuns are repeating the word Om, Om, she distributes minium among her relations, and her jewels among the priests. To those who assist at the ceremony, she throws some grains of rice as she proceeds three times around the pile on which the corpse of her husband has been deposed wrapt up in a white sheet. Two Brahmuns accompany her repeating texts of the sacred writings, and representing to her the inexpressible pleasures which await her in the next world. Even the whole family of the widow are to participate of the happiness which, according to their opinions, is to be the result of this sublime action; for the Brahmuns assert that all those who lead the widow to the pile will enjoy for every step they take many years of felicity. I must refer my readers to the Memoirs of the society of Calcutta, for the religious forms and sacred sentences which are employed throughout the ceremony.

This print represents the procession round the pile: on one side are seen the banks of the river and a little temple, for the scene generally takes place in the vicinity of a pagoda. What follows will be the subject of the first print of the next number.

Commentary:

Solvyns here portrays the ritual events leading to the sacrificial self- immolation he terms "Shoho-Gomon," sahagamana, by which the widow "goes together" with her dead husband on the cremation pyre. While Solvyns assures his readers that he relies for his descriptions only on what he can verify, he appears here and in the next description of suttee, to have drawn for detail upon Colebrooke's essay in Asiatick Researches , "On the Duties of a Faithful Hindu Widow." There Colebrooke quotes from a Sanskrit source as to the ritual preparation in terms very similar to that of Solvyns: "Having first bathed, the widow dressed in two clean garments, and holding some cusa grass, sips water from the palm of her hand. Bearing cusa and tila [sesame], she looks toward the east or north, while the Brahmana utters the mystic word Om."[38] Again, after quoting various Sanskrit texts, Colebrooke ends with a description by an unidentified witness that bears close resemblance to Solvyns's account: "Adorned with all jewels, decked with minium and other customary ornaments, with the box of minium in her hand, having made puja, or adoration to the Devatas [gods], thus reflecting that this life is nought: my lord and master to be was all,--she walks round the burning pile; she bestows jewels on the Brahmanas, comforts her relations, and shows her friends the attention of civility, while calling the Sun and elements to witness, she distributes minium at pleasure; and having repeated the Sancalpa [samkalpa],[39] proceeds into the flames; there embracing the corpse, she abandons herself to the fire, calling Satya! Satya! Satya! "[40]

The print depicts the woman, soon to become sati, escorted toward the pyre by two brahmins. She wears a white sari draped over her left shoulder, revealing bare breasts but the exposure seems at odds with the modesty of brahmin and higher sudra caste women in Bengal. Reflecting his own observations, Solvyns frequently depicts lower caste women with only partially covered breasts, but suttee was largely confined to higher caste women. The Hodges engraving, by contrast, shows the wife with fully covered breasts. Paul B. Courtright, who has written on the representation of sati, wonders whether Solvyns might here have succumbed to the romance of orientalism. "In European art of the period, . . . semi-nude portrayals of women were commonplace, especially in representations of 'natives' from exotic parts of the world."[41]

The attending priests are Vaisnavites, as indicated by the faintly etched tilak (sectarian mark) on the forehead, seen most clearly in the Paris edition, where it is colored in vivid ocher.

Many of Solvyns's etchings were reproduced, as was this print, usually without attribution, in various books on India published during the nineteenth century.[42] Indeed, reproduction of Solvyns's representations of suttee may have played an important role in shaping the visual image of the practice in the European mind.

Anumarana, Anumrta

Calcutta: Sec. XII, No. 14. Onnoo-Gomon, or Onno-Mutah,--this represents the Wife burning herself with some apparel or property of her husband, when he had died in a distant country, or in the instance of her being prevented [from] devoting herself at the time of her husband's Corpse being burnt, by his decease happening during her pregnancy, or at the period of sexual indisposition.--The great advantage of this sacrifice is supposed to be, that it liberates both parties from Hell, and entitles them to millions of years of bliss in Heaven.--Priestcraft, in gaining its ends, looks with indifference on the sacrifice of the lives of the ignorant; and private calamities and nations deluged in blood, as tending to establish its power, must be regarded with equal unconcern, if not satisfaction:--but religious frenzy will now perhaps give way to political fanaticism.

Paris: II.10.1: ONNOO-GOMON, OR ONNOO-MUTAH.

THE WIFE BURNING HERSELF WITH SOME OF HER HUSBAND'S PROPERTY

After walking thrice round the pile, the widow ascends it with courage, places herself by the side of her dead husband and cries out three times satiah [satya ] . At the same instant fire is set to the wood which is always raised a little above the ground. Dried leaves, oil, melted butter gue [ghee], (a kind of) and all sorts of combustible matters are thrown upon the pile, to put a speedier period to her sufferings. Her body is kept from moving by two bambous;[43] the flames reach it instantaneously, and in a few minutes she is consumed.

In general, this dreadful act is performed a few hours after the decease of her husband: but if he dies in distant country, it is differred on the contrary for some months, which puts the widow to a much severer trial, since during all that time she has constantly before her eyes the horrid fate which awaits her. Until the fatal period arrives, she has constantly upon her some part of the apparel, a sandal, or some other object which her husband used to wear. In all other respects, the ceremony is exactly the same as that which we have described. It must however be remarked that every country in India has some particular custom of its own, beyond what is sanctioned by the law; but the essential points are everywhere the same.

By the sacred writings this voluntary death is forbidden to women giving suck, to those who are under periodical indisposition, or who are with child, or may be supposed to be so. Except in these cases, every widow is obliged to burn herself, unless she prefers to live as a slave in her own house, to perform the meanest offices, or to become a prostitute in the public places, an outcast from all respectable society, and abandoned by her family. They have but one way to escape the infamy of such a situation, which is to become exiles in the desert, and lead the life of those Agoorees [44] of whom I have given a description in the second number of this volume.

It is believed in Europe, upon the word of some travellers, that the horrid ceremony represented in this print is totally out of use. It is true that examples of it are less frequent than formerly; but whoever travels at all in the Hindoo country, may still be witness of it. The English government wished to abolish this cruel custom, and the execution of it has frequently been prevented by military interference:[45] but these measures, dictated by humanity, have only rendered the Hindoos more circumspect, and they perform in secret what they are not allowed to do publicly. The widows still burn themselves with their husbands, and the death of an Hindoo is sometimes followed by the voluntary suicide even of all the women whom he kept.[46]

Commentary:

If the husband dies at some distance and is cremated there or if the suttee is postponed for some reason, the immolation of the widow is known as anumarana , "dying after," or anugamana, "going after" or "to follow," as here in death. Anumrta is "one who has followed her husband in death." Solvyns uses the terms "Onnoo-gomon" and "Onnoo-mutah."

In his account of suttee, Thompson writes that anumarana "was the term used when her lord died and was burned at a distance from her--during a campaign perhaps, or when her own death was postponed because she was pregnant; she was then burned with something that belonged to and represented her husband--his shoes or turban or some piece of clothing."[47] Various factors might result in the postponed suttee, and there are cases of widows going to the pyre as long as fifteen years after their husbands' death.[48]

Even as the British government in India reaffirmed its policy against interference in matters of the Hindu religion, suttee came under increasing official scrutiny in the early nineteenth century. In 1817, the government ruled that Hindu law did not permit brahmin widows "to ascend any other pile than that of their husbands" and that, consequently, they "could not be allowed to perform the rite of anumarana, or of burning after their husband's death and at a different time and place, but that they could only be allowed to perform the rite known as sahamarana, or burning on the same funeral pile."[49]

In the print, Solvyns depicts two attendants holding down bamboo poles as restraints in the manner described in the 1785 account "By an Officer" of the suttee he witnessed: After the wife had been secured on the pyre and "everything was ready, her eldest son came and set fire to the under part of the straw: in a moment all was in a blaze. Two men kept a very long bamboo closely pressed upon the bodies . . . ."[50] In 1799, the missionary William Carey, on witnessing a suttee for the first time, wrote: "She in the most calm manner mounted the pile. . . . She lay down on the corpse, and put one arm under its neck and the other over it, when a quantity of dry cocoa-leaves and other substances were heaped over them to a considerable height, and then Ghee or melted preserved putter, poured over the top. Two bamboos were then put over them and held fast down, and the fire put to the pile. . . ."[51]

Sahagamana

Calcutta: Sec. XII, No. 15. Shoho-Gomon,--representing the Woman leaping into the fire to the Corpse of her Husband, or to some relict of the deceased,--this is allowed equally with the other modes, but seldom practiced in Bengal.

Paris: II.11.1:SHOHO-GOMON.

A WOMAN LEAPING INTO THE FLAMES TO THE CORPSE OF HER HUSBAND.

This is a custom which seldom takes place in the countries of Hindoostan where I have chosen the greater part of the subjects of my prints. But as I was myself once present at it, I had an opportunity of making a drawing of this ceremony with all its circumstances. It seemed to me more cruel than what I have described in two foregoing numbers, and indeed it is most in vogue among the warlike tribes of the Mahrattas and Seics [Sikhs].

The widow whom I saw burn herself, was in the first bloom of youth: she appeared nevertheless full of courage and resolution: the attending Brahmuns entertained her with their pious addresses as they led her to the pile where she jumped without the smallest signs of fear, and while she was yet crying out three times salya [satya] the flames surrounded her: her friends and relations then threw upon her different combustible matters, and in five or six minutes her body was entirely consumed; some few bones remained which were gathered up and reduced to ashes. When the dreadful ceremony was over, the Brahmuns returned with the family of the unhappy widow, and received as they went the compliments of the public for having performed an act of devotion from which they derive the highest consideration in the eyes of this fanatick people.

The women, especially the wives of the Brahmuns, are instigated by their blind superstition to choose this mode of death: they look upon it as a duty to evince in the midst of torture their superiority over other women whom they look upon as much beneath them. And yet it often happens that there is very little affection between the Brahmuns and their wives, to whom they are sometimes married almost against their consent. I shall mention a strange practice which I had an opportunity of observing during my stay in India. When a father of a family has a daughter of an age to be married and has not the means of making a suitable provision for her, he invites under some pretext a Brahmun of his acquaintance to his house: as soon as he appears the father presents him his daughter; she, out of respect, offers him her hand, which the Brahmun takes without any suspicion; immediately the father begins to repeat the geneology of the family: this simple ceremony is sufficient; the marriage can not be dissolved. It not unfrequently happens that the Brahmun is unable to support his young wife; be that as it may, the father has saved her from the reproach of remaining a maid, and his daughter enjoys the honors due to the wife of a Brahmun.

Commentary:

In the 1799 Calcutta edition, the woman leaping into the flames appears older, both in facial features and with somewhat drooping breasts. In the Paris edition, 1810, she is shown to be young, with small, firm breasts, and the accompanying text describes her as "in the first bloom of youth." Whether the difference lies in the comparatively crude etching of the Calcutta print, such that a young woman appears older, or in a conscious decision by Solvyns to change the figure to that of a young woman is not evident, but Solvyns drew the scene from life, and he repeatedly emphasizes his commitment to a faithful representation of what he observes. In Plate II.9.1., "A Woman Burning Herself with the Corpse of her Husband" is seen as young in the etchings of both the Caluctta and Paris edition.

Paul Courtright, in reflecting on the images of the Solvyns prints, notes that the erotic display of bare breasts runs through many representations of suttee by European artists. Moreover, he argues, "in both Hindu myths . . . and European genre of eye-witness testimony, the wife is frequently represented as young, nubile, and virginal. Within the Hindu framework youth and innocence underscore the purity and effectiveness of the sacrifice; while for the European representations the innocence of the young wife, at the mercy of relatives, priests, and superstitution, serves to stress the theme of victimization and heightens the role of the colonial as the heroic rescuer of the damsel in distress."[52]

Although European accounts of suttee typically related the sacrifice of a beautiful young woman, the practice, in reality, included women of all ages, with reported instances ranging from a girl as young as four to a 100-year-old widow, with the larger number, not surprisingly, aged 40 or above.[53]

Solvyns's vivid depiction of suttee as the woman leaps into the flames was reproduced in various publications (without attribution to the artist),[54] and it served as the model for the relief on a silver snuff box.[55] Perhaps this portrayal was favored by missionaries in their campaign against suttee because it might appear from the print alone that she is pushed by her brahmin attendant. The text makes clear, however, that she was "full of courage and resolution" and "jumped without the smallest signs of fear."

Sahagamana

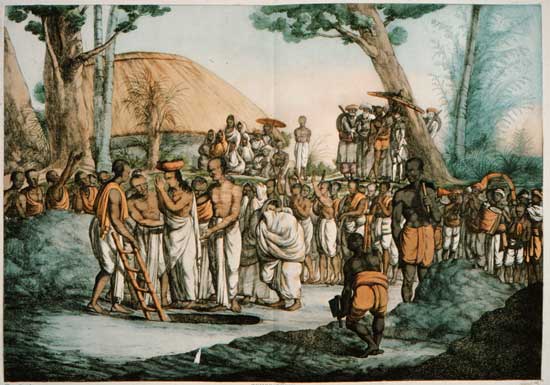

Calcutta: Sec. XII, No. 16. Shoho-Gomon,--the Wife of the Joggee buried alive with the Corpse of her Husband,--after her descending into the Pit, it is instantly filled up with earth by her relations and other attendants.--The Joggee, and the race of Facquirs, called Visnubs [Baisnabs, Vaisnavas], are the only classes of the Hindoos, whose bodies are buried.

Paris: II.12.1: SHOHO-GOMON.

THE WIFE OF AN HINDOO BURIED ALIVE.

Besides the Faquirs and Beeshnubs [Baisnabs, Vaisnavas], the Joogees [Jugis], dealers in cloth and weavers, are the only people among the Hindoos who bury their dead: the cruel custom therefore of widows burying themselves alive with the bodies of their husbands, exists only in this division of the working cast, and is confined moreover to the country of Orissah and that of the Marattas. Travellers who visit only Bengal and Behar have very seldom an opportunity of witnessing these fanatic ceremonies, which I shall describe exactly as I saw them. When the widow of a Joogee has signified her intention to bury herself with her deceased husband, her family dig a grave from six to eight feet deep, into which the body of the husband is let down, and placed sitting with the hands joined. The widow then approaches the grave, escorted as in the ceremonies which we have already described by a solemn procession. She bathes before the public without giving occasion to the slightest scandal, being already considered, from the sanctity of the death she has chosen, as a supernatural being. At the edge of the grave she listens to the pious exhortations of the Brahmuns who accompany her, gives them her jewels, and after placing upon her head a cudjery [khicuri][56] or pot filled with rice, plantains, betel and water, makes her farewell salutations to the assistants with her hands joined. She descends into the grave by a ladder of bambou which is instantly drawn up again. She seats herself by the side of her husband; at that moment all the instruments hired for the ceremony are heard, and the relations throw such quantities of earth upon the unfortunate widow, that she is soon suffocated and interred. The preparations for this ceremony are horrid, but it does not appear that the sufferings of the unhappy victim are of long duration.

The print is an exact copy of what I observed; even the little eminence is there, from which I witnessed this scene: but the pencil can not convey the dreadful sensations it gave rise to. We can not refuse our pity to the poor Hindoo women who are sacrificed to this ancient and barbarous custom; but their courage, firmness, and resignation, entitles them to some share of admiration. While their husband lives they are slaves, when he dies they must be ready to resign in the most cruel manner a life of which they never tasted the enjoyments. In no part of the universe are women born to so dismal a prospect.

Commentary:

Few European accounts of suttee make reference to the burial of the widow with her husband, and Solvyns provides a comparatively rare description[57] and perhaps the only visual depiction of the rite.[58] In his portrayal, the widow stands with her palms together in an attitude of devotion as she prepares to join her husband. In the Calcutta etching, depicted here, she is bare-headed, but in the Paris print, Solvyns, in conformity with his descriptive text, places a khicuri pot upon her head. He depicts a grave that is circular and a ladder by which the widow will descend.[59] The musicians are seen to the back right in the print, and a European--perhaps a Company official--stands shaded by an umbrella and attended by several guards as he watches the ceremony.

Ward, as does Solvyns, notes that widows of the Jugi (Joogee for Solvyns; Yogee for Ward) community--a caste of weavers--were sometimes buried alive with their deceased husbands. "If the person have died near the Ganges, the grave is dug by the side of the river; at the bottom of which they spread a new cloth, and on it lay the dead body. The widow then bathes, puts on new clothes and paints her feet, and after various ceremonies, descends into the pit that is to swallow her up; in this living tomb she sits down, and places the head of her deceased husband on her knee, having a lamp near her. The priest (not a bramhun) sits by the side of the grave, and repeats certain ceremonies, while the friends of the deceased walk round the grave several times [repeating incantations. The friends cast various offering into the grave.] The son also casts a new garment into the grave, with flowers, sandal wood &c. after which earth is carefully thrown all round the widow, till it is has risen as high as her shoulders, when the relations throw earth as fast as possible, till they have raised a mound of earth on the grave, when they treat it down with their feet, and thus bury this miserable wretch alive . . . ."[60]

Most Hindus are cremated, but burial is used among some caste communities, most notably in South India, and for certain classes of individuals--religious acetics (yogis, sadhus, and sannyasis), young children, and those who die by violence or with such diseases as cholera or small-pox.[61] The Jugis, however, seem to have been alone--at least in Bengal--in suttee burial. Mythically, the Jugi weavers claim descent from an ascetic, who on his death was buried, following the custom for yogis. Risley, in The Tribes and Castes of Bengal, writes that "On the burial of their dead all Jugis observe the same ceremonies. The grave . . . is circular, about eight feet deep, and at the bottom a niche is cut for the reception of the corpse. The body, after being washed with water from seven earthen jars, is wrapped in new cloth, the lips touched with fire to distinguish the funeral from that of a sannyasi or ascetic and a Mahomedan. . . . The body being lowered into the grave, and placed in the niche with the face towards the north-east [sacred to Siva], the grave is filled in . . . ."[62] By the time of Risley's account in 1891, suttee among the Jugis (to which he makes no reference) had long been suppressed.

In 1813, there was an official inquiry into the Jugi practice of burial suttee. The case involved a Jugi woman who, "at her own request," asked to be buried with her husband. British officials, consulting Pundits on their reading of the Dharma Sastra, Hindu legal text, determined that "the practice was in conformity with the Shasters" and that it was not to be enjoined.[63] But with mounting pressure for reform, in 1829, the Governor-General, Lord Bentinck, outlawed "the practice of suttee; or of burning or burying alive the windows of the Hindoos. . . ."

Notes

*Reproduced here with permission of the publisher, Bengal Past and Present (Kolkata).

1 Born Francois Baltazard Solvyns, he used his middle name, Baltazard, rather than Francois. On Solvyns, see Mildred Archer, "Baltazard Solvyns and the Indian Picturesque," The Connoisseur l70 (January l969), pp. l2-l8, and Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr., "A Portrait of Black Town: Baltazard Solvyns in Calcutta, l79l-l804," in Pratapaditya Pal, ed., Changing Visions, Lasting Images: Calcutta Through 300 Years (Bombay: Marg, l990), pp. 3l-46. The full collection of Solvyns's etchings, together with introductory chapters on his life and work, will appear in Hardgrave, A Portrait of the Hindus: Baltazard Solvyns in Calcutta, l79l-l804, forthcoming.

2 John S. Hawley, "Introduction," in Sati, the Blessing and the Curse: The Burning of Wives in India (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, l994), pp. l2-l3; Edward Thompson, Suttee (London: George Allen & Unwin, l928), p. l5; V. N. Datta, Sati: A Historical, Social and Philosophical Enquiry into the Hindu Rite of Widow Burning (New Delhi: Manohar, l988), p. l; Sakuntala Narasimhan, Sati: A Study of Widow-Burning in India (New Delhi: Viking, l990), p. l9. On the woman's duty to die with her husband, see I. Julia Lesie, The Perfect Wife: The Orthodox Hindu Woman according to the Stridharmapaddhati of Tryambakayajvan (Delhi: Oxford University Press, l989), pp. 291-98. On suttee more generally, there is an extensive literature. See especially Ajit Kumar Ray, Widows are not for Burning (New Delhi: ABC Publishing House, l985), Hawley, and Datta.

3 Socioeconomic Impact of Sati in Bengal (Calcutta: Naya Prakash, l987), pp. 43-48.

4 From l8l5 until its abolition in l829, the government kept records of reported suttees in Bengal. The practice may well have been most frequent among brahmins, but the various sudra castes together (principally those of higher status) accounted for the majority of instances of suttee. Amitabha Mukherjee, Reform and Regeneration in Bengal, l774-l823 (Calcutta: Rabindra Bharati University, l968), pp. 244-50. Considerable controversy attends the discussion of the increased reports of suttee in Bengal in the late l8th and early l9th centuries. See, for example, Asis Nandy, "Sati: A Nineteenth-Century Tale of Women, Violence and Protest," in At the Edge of Psychology: Essays in Politics and Culture (Delhi: Oxford University Press, l980), pp. l-3l, and Ainslie T. Embree, "Widows as Cultural Symbols," in Hawley, pp. l49-59.

5 Pierre Sonnerat, A Voyage to the East Indies and China [tr. from the French by m. Magnus] (Calcutta: Stuart and Cooper, l788), Vol. I, pp. ll2-l9. The engraving appears only in the original French edition, Voyage aux Orientales et a la Chine (Paris: L'Auteur, l782), Vol. I, Pl. l5 (opp. p. 95).

6 L. De Grandpre, A Voyage in the Indian Ocean to Bengal, Undertaken in the Year l789 and l790 [tr. of the l80l French edition] (London: G. & J. Robinson, l803), Vol. II, pp. 69-74.

7 Travels in India a Hundred Years Ago (London: James R. Osgood, l893), pp. 463-67, in H. K. Kaul, ed., Travelers' India: An Anthology (Delhi: Oxford, l979), pp. 92-96.

9 February l0, l785, reprinted in W. S. Seton-Karr, Selections from Calcutta Gazettee of the years l784, l785, l786, l787, and l788 (Calcutta: Military Orphans Press, l864), Vol. I, pp. 89-9l. Also reproduced in Kathleen Blechynden, Calcutta Past and Present (ed. by N. R. Ray) (Calcutta: General, l978 [l905]), pp. l90-93.

10 A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos, new ed. (London: Black, Kinsbury, Parbury & Allen, l822), Vol. III, pp. 308-30. [Reprinted Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, l970] Also see Ward, Account of the Writings, Religion, and Manners of the Hindoos (Serampore: Missionary Press, l8ll), Vol. II, pp. 544-66. On missionary efforts to suppress suttee, see E. Daniel Potts, British Baptist Missionaries in India, l793-l837: The History of Serampore and its Missions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, l967), pp. l44-57.

11 Susan S. Bean, Yankee India: Commercial and Cultural Encounters in the Age of Sail, forthcoming.

12 From "Log of the 'Henry,' Nov. 28, l789." Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Quoted in Bean, Yankee India.

13 Letters on India (London: Longman et al, l8l4), pp. 303-06. Maria Graham, also known as Lady Callcott, was surely a remarkable woman for her time in India. These letters--discourses on Indian religion, art, and manners--reveal her as perhaps the first woman Orientalist.

14 The distinction reflected the view held by most eighteenth century orientalists that the practice was sanctioned in Hindu religious texts. See Rosane Rocher, "British Orientalism in the Eighteenth Century: The Dialectics of Knowledge and Govrnment," in Orientalism and the Postcolonial Predicament: Perspectives on South Asia, edited by Carol A. Breckenridge and Peter van der Veer (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, l993), p. 230.

Under regulations adopted in l8l2, authorities were to preclude, as far as possible, instances of "illegal" suttee, deemed by the government repugnant to Hindu law, such as those involving the use of drugs or compulsion. These and subsequent regulations before the final abolition of suttee are examined in "Suttee," Calcutta Review 92 (l867), pp. 221-6l. See especially pp. 227-29. The article is based on a series of parliamentary (House of Commons) papers, running to several hundred pages, published between l82l and l825. For a listing of the papers see Hansard's Catalogue and Breviate of Parliamentary Papers [l699-l824], p. 98.

On movement to suppress suttee, see Mukherjee, pp. 238-85, and on the official debates, Lata Mani, "The Production of an Official Discourse on Sati in Early Nineteenth-Century Bengal," in Francis Barker, et al, eds., Europe and Its Others (Colchester: University of Essex, l985), Vol. I, pp. l07-27, and Lata Mani, "Contentious Traditions: The Debate on Sati in Colonial India," in Kumkum Sangari and Sudesh Vaid, eds., Recasting Women: Essays in Indian Colonial History (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, l990), pp. 88-l26.

15 Datta, p. l05. The text of the Regulation is in Datta, Appendix II, pp. 25l-53.

16 Linschoten's Itineraro, first published in Dutch in Amsterdam in l596, was the most important Dutch book on Asia in this period and went through l5 reprints and translations in the seventeenth century. The engraving, Pl. 20, "A Suttee," appears in the English translation, John Hvighen van Linschoten, His Discours of Voyages into ye Easte and West Indies, translated from the Dutch by William Phillip (London: John Wolfe, l598). The print is not included in the reprint edition, The Voyage of John Huyghen van Linschoten to the East Indies, edited by Arthur C. Burnell and P. A. Tiele, 2 vols. (London: Hakluyt Society, l885; New Delhi: Asian Educational Services, l988). On Linschoten, see Donald F. Lach and Edwin J. Van Kley, Asia in the Making of Europe (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, l993), Vol. 3, Bk. 2, pp. 435-36, 549.

17 Theatre de L'Idolatrie ou la Porte Ouverte, Pour parvenir a la connoissance du Paganisme Cache. French translation of De Open-deure tot het Verborgen Heydendom, from the Dutch by T. LaGrue (Amsterdam: Chez Jean Schipper, l670). The original edition, published in Leiden in l65l, does not have the engraving. The print is reproduced in Lach and Van Kley, Vol. 3, Bk.2, Pl. l97.

For Roger's description "of those women who are burnt or buried with their Husbands," see "A Dissertation on the Religion and Manners of the Brahmins," in Bernard Picart, ed., The Religious Ceremonies and Customs of the Several Nations of the Known World (London: l73l), Vol. III, pp. 334-6.

18 The painting is in the Oriental Club, London, and is reproduced in Mildred Archer and Ronald Lightbrown, India Observed: India as Viewed by British Artists, l760-l860 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, l982), Plate 2, p. 33, and in Mildred Archer, India and British Portraiture l770-l825 (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, l979), Plate 27, p. 7l.

19 The painting is reproduced, with Tillotson's commentary, in C. A. Bayly, ed., The Raj: India and the British l600-l947 (London: National Portrait Gallery, l990), Plate 278, p. 22l. Zoffany's fascination with suttee is further evidenced by his inclusion of paintings of suttee in the backgrounds of two group portraits.

20 Travels in India, During the Years l780, l78l, l782, and l782, 2d ed. (London: By the Author, l794), pp. 79-83.

21 See p. ---. [Manuscript p. 9]

22 Archer and Lightbrown, p. l33. The painting is reproduced Plate l3l, p. l32.

23 Reproduced in Bayly, The Raj: India and the British l600-l947, Plate 279, p. 222.

24 Paul B. Courtright discusses changes in the visual representation of suttee in The Goddess and the Dreadful Practice The Immolation of Wives in the Hindu Tradition and its Western Interpretations (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming), and in "The Iconographies of Sati," in Hawley, pp. 27-53.

25 Balt. Solvyns, A Collection of Two Hundred and Fifty Coloured Etchings: Descriptive of the Manners, Customs, and Dresses of the Hindoos (Calcutta; l796, l799).

26 See Robert L. Hardgrave, Jr., and Stephen M. Slawek, Musical Instruments of North India: Eighteenth Century Portraits by Baltazard Solvyns (New Delhi: Manohar, l997).

27 (London: Edward Orme, l804, l807).

28 Les Hindous (Paris: Chez L'Auteur, l808), Vol. I, p. 29.

29 F. Baltazard Solvyns, Les Hindous, 4 vols. (Paris: Chez L'Auteur, l808-l8l2).

32 Solvyns, A Catalogue of 250 Coloured Etchings; Descriptive of the Manners, Customs, Character, Dress, and Religious Ceremonies of the Hindoos (Calcutta: Mirror Press, l799).

33 See particularly Henry. T. Colebrooke, "On the Duties of a Faithful Hindu Widow," Asiatick Researches, 4 (l795), pp. 205-l5. The essay was presented to the Asiatic Society Calcutta, in l794.

34 Hodges, in Travels in India , describes a suttee he witnessed near Banaras, with an accompanying engraving, "Procession of a Hindoo Woman to the Funeral Pile of Her Husband." (London: By the Author, l793), pp. 79-83. The plate is reproduced as the frontispiece and as the cover for the paperback edition in Hawley.

35 The pamphlet is not in the India Office Library or other libraries consulted nor is it cited in the bibliographies of the many books on suttee. The name "Shakespeare" does not appear in C. H. Philip's "List of Directors." The East India Company l784-l834 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, l96l), pp. 335-37. Too early to be John Shakespear (l774-l858), author of an l8l2 Hindustani grammar, perhaps Solvyns's author is Colin Shakespear, who designed the bridge over Tolly's Nullah in Calcutta and served as Postmaster General. Arthur W. Devis painted his portrait, c. l790, reproduced in Narendra Kumar Nayak, ed., Calcutta 200 Years: A Tollygunge Club Perspective (Calcutta: Tollygunge Club, l98l), p. 64.

36 Latin, native cinnabar; a red, or vermillion, mercuric sulfide used as a pigment. A color sacred to the Greeks as well as Hindus.

37 The most sacred of Indian grasses, more commonly called darbha, kusa (Eragrotis cynosuroides) is required in various Hindu rituals.

39 Samkalpa , meaning, in this context, a vow or declaration of the widow to burn herself with her deceased husband. Sir Monier Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, l899), p. ll26.

40 Colebrooke, pp. 2l4-15. The word satya is Sanskrit for "truth." For detailed descriptions of the ceremonial preparations for suttee, see Zakiuddin Ahmed, "Sati in Eighteenth Century Bengal," Journal of the Asiatic Society of Pakistan, l3 (August l968), pp. l57-58, and Amitabha Mukhopadhyay, "Sati as a Social Institution in Bengal," Bengal Past and Present 76 (l975), pp. l04.

41 Personal communication, June 4, l993. See his "The Iconographies of Sati," and The Goddess and the Dreadful Practice.

42 Engravings after this Solvyns print appeared as "Gentoo Widow Going to be Burnt with her Dead Husband," in William Ward, A View of the History, Literature, and Religion of the Hindoos (Hartford: H. Huntington, l824), Vol. I, opp. p. 375; and in Frederic Shoberl, ed., The World in Miniature: Hindoostan (London: R. Ackermann [l822]), Vol. III, No. 40, opp. p. 99. An anonymous colored etching from l8ll (V4l9l0) in the collection of the Wellcome Institute, London, depicts Solvyns's central figures, the widow and her two brahmin attendants, in a composition with a scene of the pyre by another artist.

43 Thompson, in writing of suttee, pp. 40-44, notes that "She was by no means always left free [on the pyre]. Especially in Bengal, she was often bound to the corpse with cords, or both bodies were fastened down with long bamboo poles curving over them like a wooden coverlet or weighted down by logs." In a footnote, he refers to Rammohan Roy in l8l8 saying this custom was a recent innovation and confined to Bengal.

44 Aghoris, mendicants who are "without terror" of the impure.

45 In a compendium of offical accounts of suttee reported by the East India Company, from Fort William in Calcutta, the British House of Commons paper relating to "Hindoo Widows and Voluntary Immolations" relates instances of official intervention. Great Britain. Parliamentary (House of Commons) Sessional Papers, l8 (l82l), pp. 295-565. This was sometimes undertaken unofficially, as in Grandpre's unsuccessful attempt to prevent a suttee. A story long associated with Job Charnock, who founded Calcutta in l690, is that he rescued a beautiful l5-year-old girl from her husband's pyre, took her under his protection, and married her. See Alexander Hamilson, New Account of the East Indies (London: Argonaut Press, l930 [l727]), Vol. II, p. 5; and P. Thankappan Nair, Job Charnock: The Founder of Calcutta (Calcutta: Engineering Press, l977), pp. 27-28.

46 In l799, in a village near Nadia, not far from Calcutta, 37 women became sati on the pyre of a kulin brahmin. "At the first kindling of the fire only three of his wives were present; so the fire was kept burning for three consecutive days, while relays of widows were fetched from a distance." Mukherjee, p. 24l. (Kulin polygamy involved the practice of high caste brahmins, in effect, selling themselves as husbands to a large number of women, whom they then visited in rotation. Mukherjee, p. 242.)

47 Suttee, p. l5. Also see, V. N. Datta, p. l, and Narasimham, p. l9.

48 Amitabha Mukhopadhyay, p. l02.

49 "Suttee," Calcutta Review, p. 228.

50 Calcutta Gazette , February l0, l785. Seton-Karr, p. 9l.

51 Quoted in George Smith, The Life of William Carey (London: John Murray, l885), p. l08.

52 Personal communication, June 4, l993.

53 Mukherjee, p. 25l. Walter Hamilton provides statistics on age for the year l823: Of 575 women who performed suttee in Bengal, 32 were below the age of 20; 208 between 20 and 40; 266 between 40 and 60; and l09 over 60. East India Gazetteer, 2nd ed. (London: Parbury, Allen & Co., l828), Vol. I, pp. 205-06.

54 Engravings of this Solvyns plate appear in Ward, A View of the History, Literature, and Religion of the Hindoos, Vol. I, opp. p. 392; in Missionary Papers [Church Missionary Society, London], No. 34 (l824), and in First Ten Years''Quarterly Papers of the Church Missionary Society (London: Seeley & Son, l826). Paul Thomas, Hindu Religion, Custom and Manners (Bombay: D. B. Taraporevala Sons, l960), Pl. 93, reproduces the Solvyns print from the Paris edition.

55 A silver snuff box, British India, l820-l830, with one side depicting Solvyns's "woman leaping into the flames," was exhibited in the Peabody-Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. I am grateful to Paul Courtright for drawing my attention to this item. The box is now in a private collection, but similar boxes have come onto the market from time to time.

56 Solvyns uses the Bengali term for a one pot dish of rice, dhal, and vegetables that is often used as a ritual offering. Hobson-Jobson lists kedgeree-pot as a vulgar Anglo-Indian expression for a pipkin, or small earthenware cooking pot, with Solvyns as a reference in usage. Henry Yule and A. C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (2d ed.) (Sittingbourne, Kent: Linguasia [l903]), p. 477.

57 Shoberl, Vol. II, pp. l27-29, acknowledging his source, follows Solvyns's description almost word for word, but, oddly, adds that burial suttee "is followed only is Orissah and the Mahratta country, by widows of cloth-dealers and weavers."

58 Solvyns's print is copied, without acknowledge, in an engraving in Missionary Papers [Church Missionary Society], 32 (l823) and is reproduced in First Ten Years' Quarterly Papers of the Church Missionary Society.

59 Solvyns's depiction of a circular grave is confirmed by later descriptions and confirms the link of the Jugi weavers to the yogi mendicants, who also bury their dead in circular graves, described by George W. Briggs, Gorakhnath and the Kanphata Yogis (Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, l973 [l938]), p. 40. Johan Splinter Stavorinus, a Dutch admiral, however, after describing a widow-burning he witnessed in Bengal in about l770, provides an account of a suttee burial in which the woman "jumps" into a pit that is six foot square. Voyages to the East Indies [l768-7l] , tr. from Dutch by S. H.Wilcocke, (London: G.G. & J. Robinson, l798), Vol. I, p. 45l.

60 Ward, Vol. III, p. 323. Perhaps the most detailed account of a Jugi suttee burial is by Captain Kemp in l8l3, related in a compilation of accounts of "Widows and others Buried Alive," in William Johns, A Collection of Facts and Opinions Relative to the Burning of Widows with the Dead Bodies of their Husbands and to other Destructive Customs Prevalent in British India (Birmingham: W. H. Perarce, l8l6), pp. 67-68. Suttee among Jugis is also described in Ambitabha Mukhopadhyay, pp. l04-05.

61 Burial among acetics is based on the theory that they have renounced their household fires and thus have no fire for cremation, but there is also a popular perception that they are not truly dead. See Briggs, pp. 39-43. With variation in practice among regions and castes, children below the age of three are buried rather than cremated because they are not yet fully "persons." See Jonathan P. Parry, Death in Banaras (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, l994), pp. l84-88, and P. V. Kane, History of Dharmasastra (Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, l953), Vol. IV, pp. 227-3l.

62 Herbert H. Risley, The Tribes and Castes of Bengal (Calcutta: Bengal Secretariat Press, l89l), Vol. I, p. 359.

63 See Great Britain. Parliamentary (House of Commons) Sessions Papers, l8, (l82l), pp. 332-33.