They still sing of him--in the cantinas and the country stores, in the ranches when men gather at night to talk in the cool dark, sitting in a circle smoking and listening to the old songs and the tales of other days. Then the guitarreros sing of the border raids and the skirmishes, of the men who lived by the phrase, "I will break before I bend."

They sing with deadly-serious faces, throwing out the words of the song like a challenge, tearing savagely with their stiff, calloused fingers at the strings of the guitars.

And that is how, in the dark quiet of the ranches, in the lighted noise of the saloons, they sing of Gregorio Cortez.

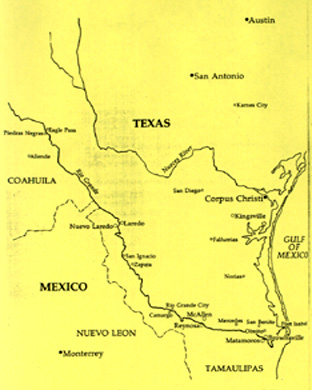

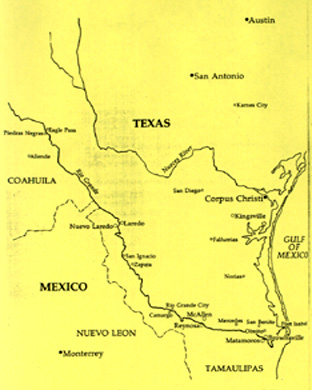

Gregorio Cortez was born on a ranch between Matamoros and Reynosa on the Mexican side of the border, on June 22, 1875, according to the best available information, the son of Román Cortez Gara and Rosalia Lira Cortinas. In 1887 the family moved to Manor, Texas, and two years later Gregorio and his older brother Romaldo began working as farm hands as well as vaqueros for farmers and ranchers in Karnes, Gonzáles, and adjacent counties.

He married Leonor Díaz at an early age, their first child, Mariana, coming along in 1891 when Gregorio was only sixteen. After years of wandering, Romaldo and Gregorio finally decided to settle down in Karnes County. It was 1900; Gregorio was twenty-five.

The following year, June 12, 1901, Sheriff T. T. (Brack) Morris came out to the Cortez place seeking a horse thief described only as "... a medium-sized Mexican with a big red broad-brimmed Mexican hat." Paredes continues the narrative as follows:

"As an interpreter, Morris had one of his deputies, Boone Choate, who was supposed to be an expert on the Mexican language. Choate appears to have been one of those men who build up a reputation for knowing the Mexicans better than they know themselves on a few bits of broken Spanish and a lot of `experience.' A number of people might not have died had Choate either known more Spanish or known enough to know what he did not know."

Through Boone Choate, Sheriff Morris questioned several Mexicans finally arriving at a man by the name of Andres Villarreal, who recently traded a horse for a mare from Gregorio Cortez. Later investigations proved that Cortez had legally acquired the mare.

Accompanied by Boone Choate and John Trimmell as deputies, Morris drove out to discuss the mare with the Cortez brothers. Romaldo spoke with the three visitors first, later calling Gregorio over. Choate asked Gregorio if he had traded a horse to Villarreal and Gregorio replied "no" (he had traded a mare). When Gregorio said "no," Sheriff Morris approached and told Choate to inform Romaldo and Gregorio that he was going to arrest them.

Morris apparently misunderstood Gregorio's reply, for in the next few seconds Morris shot Romaldo, shot at Gregorio and missed, and was, in turn, shot and mortally wounded by Gregorio. Boone Choate wasted no time running into the chaparral and joining up with deputy Trimmell where together they continued a hasty retreat back to the town of Kenedy.

Gregorio knew the posse would be along shortly. He and a feverish Romaldo waited in the brush until dark, finally making their way into Kenedy, where Gregorio left his brother with the Cortez family on the outskirts of town.

The San Antonio Express reported "The trail of the Mexican leads toward the Río Grande," as the posse headed in that direction. In reality, Cortez began his flight by walking north (some eighty miles Paredes estimates) in about forty straight hours. Near Ottine he hid out with another friend, Martín Robledo. Cortez probably felt he was pretty safe and would have been except for Robert M. Glover, sheriff of González County and a good friend of Morris. Glover "pressured" a Mexican woman into revealing Gregorio's destination, and shortly thereafter a posse surrounded the Robledo house. A gunfight ensued in which Henry Schnabel, a member of the posse, was killed by a drunken deputy; Cortez escaped.

This time he headed south toward the Río Grande. Still on foot, his first stop was at the home of Ceferino Flores who gave Gregorio a pistol and a mare. Pursued by bloodhounds leading a posse, the chase led across the Guadalupe River to the San Antonio River, a distance of some fifty miles as the crow flies, but Gregorio and the mare covered many times that distance. After two days and one night of steady riding, the durable little mare fell over and died. After dark Cortez located another mare and began the last lap of his ride. The little brown mare earned herself quite a reputation. For three days (pursuers estimated she covered some three hundred miles) she outran posse after posse. Hundreds of men were out looking for Cortez. Special trains moved up and down the tracks bearing men, dogs, and fresh horses. "The only hope," observed the San Antonio Express, "seems to be to fill up the whole country with men and search every nook and corner and guard every avenue of escape..."

Finally, the little brown mare gave out. In broad daylight Cortez walked into the town of Cotulla and from there followed the railroad tracks to the outskirts of Twohig, and where, by a water tank, an exhausted Gregorio Cortez lay down to sleep all night, all day, and all the next night as well.

Around noon on June 22, 1902, his twenty-sixth birthday, Cortez walked into the sheep camp of Abrán de la Gárza. He was spotted by a man named Jesús González, known as "El Teco." No doubt inspired by the one thousand dollars in reward money contributed by the governor, González led Captain J. H. Rogers of the Texas Rangers and K. H. Merrem, a posseman, to the sheep camp and shortly thereafter Gregorio Cortez, caught completely off guard, was arrested.

He was jailed in San Antonio. A long legal fight began. Funds were collected by the Miguel Hidalgo Workers' Society of San Antonio and other workers' organizations through special benefit performances, and through the sale of a broadside in Mexico City. The fund raising campaigns united Mexicans, rich and poor, throughout South Texas. Even a number of Anglo-Americans came to admire the courage, skill, and endurance of Gregorio Cortez adding their contributions to his defense.

His first trial, for the murder of Henry Schnabel, posseman at the Robledo house confrontation, began July 24, 1901. The quick guilty verdict that was expected did not materialize because one man, juror A. L. Sanders, believed Cortez innocent. (Schnabel was actually killed accidentally by another member of the posse.) Family illness forced Sanders to agree to a compromise; fifty years on a charge of second-degree murder. The charge satisfied no one, especially defendant Cortez. Juror Sander was not satisfied either. He told his story to the defense lawyers who promptly filed a motion for a new trial. The judge denied the motion.

The next trial was in Pleasanton, Cortez being sentenced to two years for horse theft, a conviction later reversed. At Goliad, Cortez was tried for the Morris murder, but the trial resulted in a hung jury. The next attempt to try the case was in Wharton County, but the district judge dismissed the case for want of jurisdiction. Finally, on April 25-30, the case was tried at Corpus Christi. The jury of Anglo-American farmers found Cortez not guilty of murder in the death of Sheriff Morris, agreeing that Morris had attempted an unauthorized arrest and that Gregorio had shot the sheriff in self-defense and in defense of his brother. The verdict was a victory, not only for Cortez, but for all Mexicans in Texas. Meanwhile Cortez had been found guilty of the murder of Sheriff Robert M. Glover of González County. The trial was conducted at Columbus and resulted in a life sentence for Cortez. He entered the Huntsville Penitentiary on January 1, 1905.

Eight years later, Cortez was given a conditional pardon by Governor O. B. Colquitt. His release was met with mixed emotions. Two months later he was in Nuevo Laredo apparently to establish residence, but the Mexican Revolution was gripping the north. Cortez joined the Huerta forces, possibly out of gratitude for those he saw as his benefactors. In the course of things he was wounded and subsequently returned to Manor, Texas, to convalesce. After his recovery he left for Anson, Texas, where he died at the home of a friend. The year was 1916; Cortez was forty one. He is buried in a small cemetery eight miles outside of Anson.

Para más información sobre este corrido, y muchísimos más, consulte la página de:

Discos ARHOOLIE

Para comentarios u otras comunicaciones:

mail@arhoolie.com

Go to "Gregorio Cortez" Pt. 1

Go to "Gregorio Cortez" Pt. 2

Return to Corridos de Texas

Return to SPN 325K Plan

Return to Jaime's Home Page